The Perils of Catching a Butterfly: A dive into the trials and tribulations of motherhood for Black, queer couples

Marquita and Dominique Leatherman have been together for 14 years. Over the last six years, they have navigated the trials of motherhood through diagnosis, IVF treatment, literature, and hope. Cierra Clark sat down with the Leathermans to learn more about their journey and to report on the narrative this couple hopes to share surrounding motherhood for queer, Black couples.

By Cierra Clark

The chemistry was always there for Marquita and Dominique Leatherman. Married in 2016, with a total of 14 years together, this couple always envisioned motherhood as the next step in their relationship. However, as they continue to navigate the challenges of their pursuit towards parenthood, what they envisioned as an easy transition has evolved into a trial of unwavering patience laden with grief.

Marquita recalls being a reserved and observant child. “I wouldn't quite say I was shy. I was quiet, but I loved to play. I loved makeup… like, I wanted to go outside and run around, and climb the trees and play football. I was active, but I was just quiet a lot.”

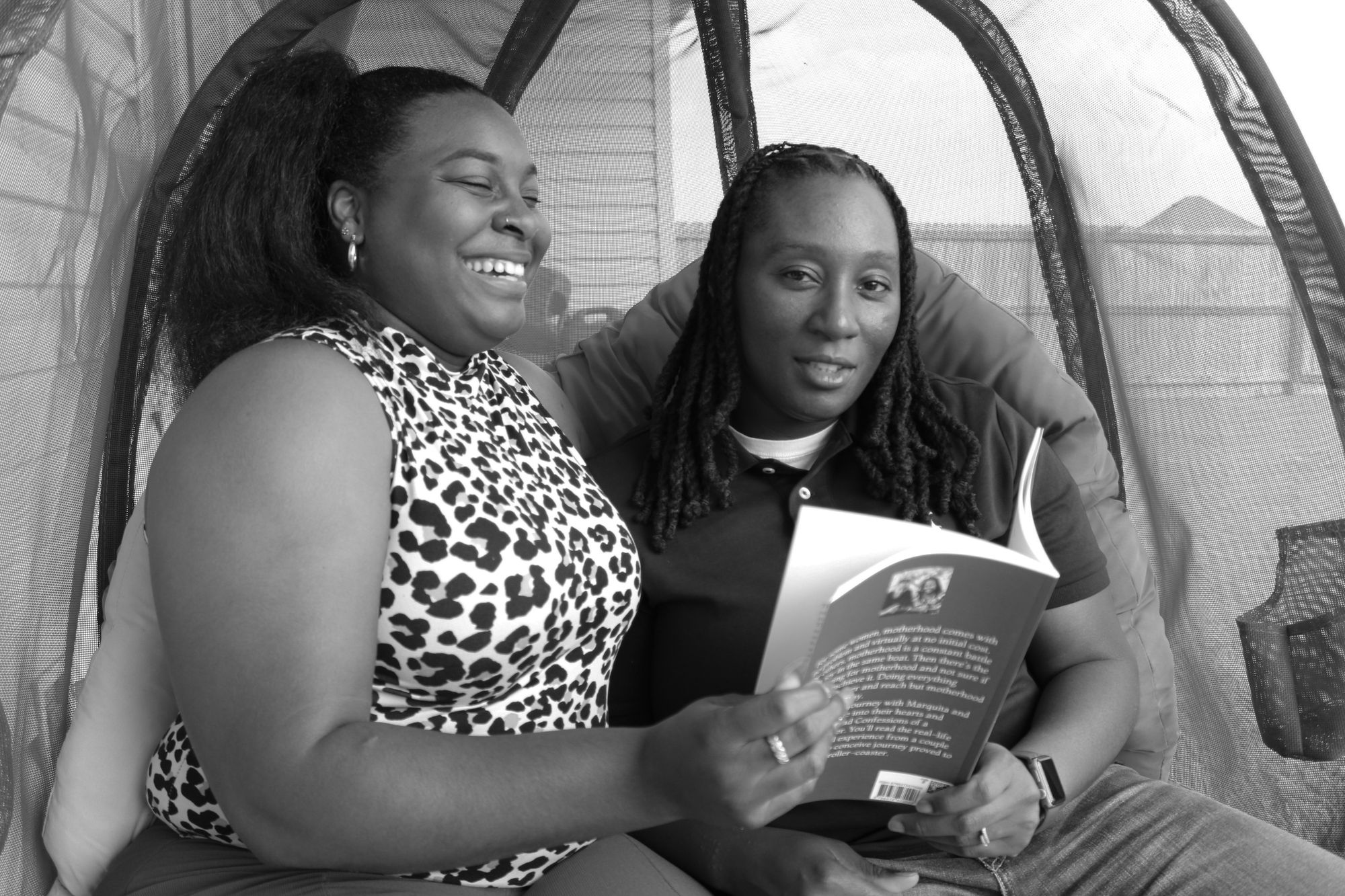

So when she decided to write the book Confessions of a Childless Mother, it often surprised people. They didn’t expect such an expressive outlet from her. Marquita and Dominique share their personal perspective on black motherhood throughout the book, shedding light on a narrative that is frequently overlooked: Infertility in Queer Couples.

According to the NIH, women in same-sex relationships experience infertility at the same rate as opposite-sex relationships–but there are unique obstacles same-sex couples face. In their book, Marquita and Dominique aim to address the challenges and complexities faced by queer couples on the path to motherhood. Despite six years of unyielding efforts, their efforts to expand their family have remained fruitless.

Marquita and Dominique began their fertility journey with home insemination from a known donor and sperm banks.

However, as time went on and their attempts yielded no success, they decided to explore alternative options. The pair turned to intrauterine insemination (IUI). The IUI procedure involves the placement of sperm, either from an anonymous or known donor, into the uterus of the partner who will carry the baby, according to the University Reproductive Associates (URA).

Although they pursued IUI, the cost associated with the procedure led them to continue home insemination in the intervals between fertility clinic visits. One cycle of IUI alone can cost anywhere between $500 to $4,000.

“The fertility clinic is when we went into the IUI. In between, because they were so expensive, we were still trying home insemination with frozen sperm from the sperm bank… it just was so much, and regardless, none of it worked. Then eventually we just moved on to in vitro,” Marquita explains, referring to IVF.

The pivotal moment in their journey occurred in 2020, when Marquita received a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Interestingly, it was not her fertility doctor who identified the condition, but rather her OB-GYN during a routine appointment.

“Once I found out, I was hurt. I felt betrayed because I was like, ‘we've been trying for almost three years,’” Marquita explains. “How did my fertility doctor not catch this, and they're the ones who do this treatment? We're going month after month, and giving all this money too. So at that point, I felt betrayed.”

Before her PCOS diagnosis, Marquita was labeled as having “Unexplained Infertility”. Marquita found herself questioning whether she had failed to advocate adequately—if she should have been more verbal in expressing her concerns, or asking more probing questions. She began to place some blame on herself, wondering if she’d been the reason it was not caught earlier.

When Marquita shared the PCOS diagnosis with her fertility doctor, they seemingly brushed it off, causing her to question their level of attentiveness. However, she did note that there were some alterations in her treatment plan, which softened some feelings of doubt towards the medical team.

“Was it that I wasn't advocating for myself enough? Was I not verbal enough about what I wanted? Did I not ask enough questions? At some point, I started to blame myself because I was like, ‘Well, you know, I brought it to my doctor's (in)attention,’” Marquita explains.

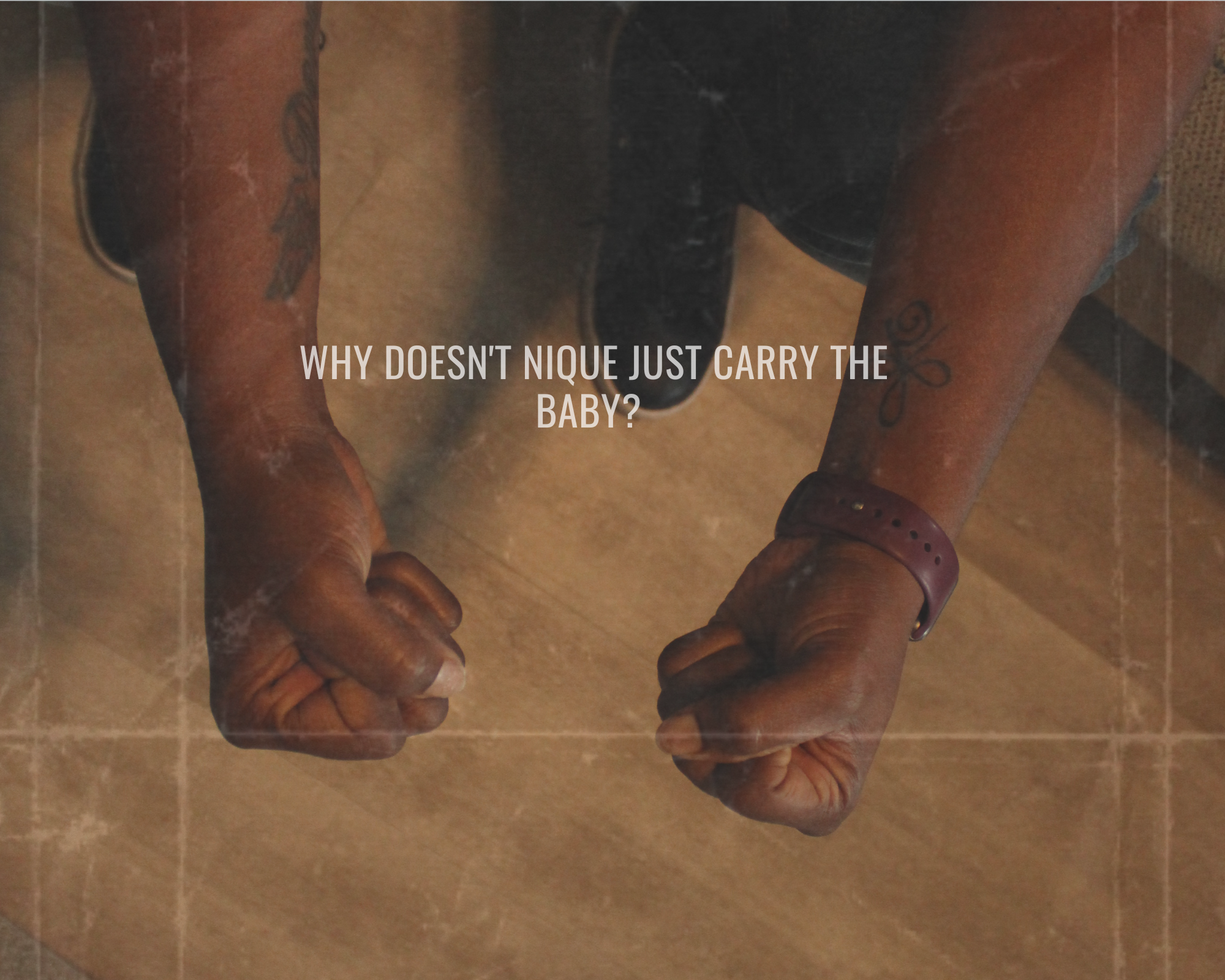

In the midst of their fertility journey, Marquita and Dominique have encountered the misconception that since both women have wombs, they can simply switch to the other partner’s.

The reality is far more complex.

The couple has invested a substantial amount of money, between $50,000 and $100,000, in their pursuit of parenthood. They have experienced firsthand the challenges and intricacies that arise for queer individuals on the path to having a baby. Unfortunately, the insensitive comments from others erase these complexities.

"Nothing is wrong with her, she's not broken,” Dominique passionately asserts. “If we wanted a surrogate, we would have asked for one, or looked for one. And if it came to a point where she couldn't carry and I needed to, I would have stepped up and done it."

Suggestions that Dominique should exclusively carry the baby not only minimize the significance of Marquita's journey, but also disregard the deep connection her wife has with her own womb. It diminishes the agency Marquita possesses in her own reproductive choices. The implication that Marquita is not “worthy” of carrying her child further erases the profound bond she has with her body.

There are multiple ways to walk into motherhood. Marquita’s desired path is to enter through being pregnant. Marquita explains there’s a connection to carrying her own baby which is fulfilling.

“It’s the nurturing part, the knowing that my body produced this little human and grew in me, and I get to feel it move around. Part of me grew within me. That's one thing I want so bad.”

In retrospect, the couple wishes they started their journey out with IVF, which has advantages other treatments do not provide. The history of IVF lets them know ahead of time what could go wrong, rather than leaving them with unknowns.

“At least knowing that we have six embryos sitting in freezers, it kind of gives me hope. If there are six babies already sitting in the freezer waiting for my body to be prepared for them, versus my body aiding those embryos and then rejecting them without me knowing.”

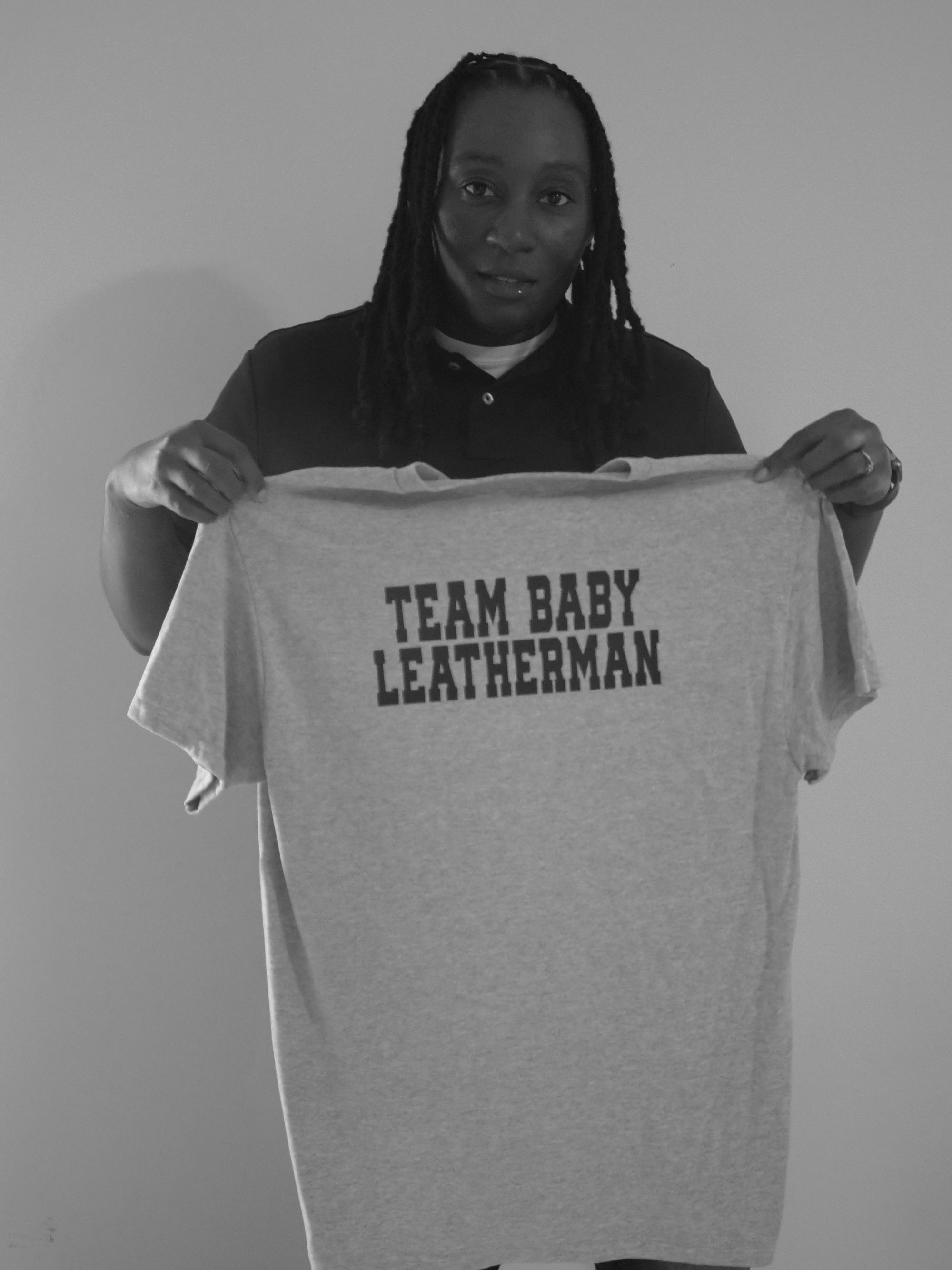

As this couple preserves through IVF, they want their future child to know they didn’t give up on them. Through these 6 years, they’ve found themselves excited through every pregnancy. Dominique states, “I want our future child, or children, to know they were always wanted, they were always needed. They were always loved. I will make sure I go through hell and back, to make sure they have everything they need and everything they want.”

In Confessions of a Childless Mother, Dominique even pens poems as Messages From Mama to their future children. In the poem Catching a Butterfly, Dominique clings to hope, reflecting on what the future will be like conceiving after many miscarriages:

“I just feel like in our situation, once we do get pregnant and have a child, it won't be a rainbow baby*. It's like catching a butterfly because you are so beautiful, yet you are so hard to catch.”

Catching a Butterfly

You are called a rainbow baby

But you are my butterfly baby

Beautiful to see yet hard to catch

One day you’ll land in my hand

And Ill put you in a jar full of love

Keeping faith you'll be coming soon

As days pass and the sun turns to the moon

Giving up isn't an option

I will keep giving your mommy strength

To keep boxing…

You are a beautiful butterfly

That seems hard to catch

That hard-to-catch is worth every shot I swing to catch you in our net

-A message from Mama

This article is available to republish under a Creative Commons license. Read Lede New Orleans’ publishing guidelines here.

Support Lede New Orleans and its community-centered reporting by becoming a supporting donor.